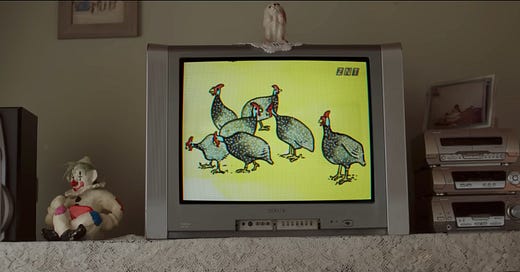

on becoming a literal guinea fowl

rungano nyoni minds her manners // two stupid articles about the decline of cinematic culture

My goal with this newsletter is to write about new films as they reach general release, along with some seasonally appropriate commentary on other cinematic events and interests. This week we’ve got Rungano Nyoni’s On Becoming a Guinea Fowl plus some complaining about a couple critical essays that have been making the rounds this month. This newsletter comes out every Wednesday, by which I mean usually every Thursday or Friday. Please enjoy - and if you do, consider sharing it with a friend.

One of my primary obsessions is the phenomenon of two objects that are functionally the same but fundamentally different. The classic example is the Catholic Eucharist, but it shows up in plenty more ecumenical spaces that I spend too much time thinking about: autobiography, conspiracy theories, celebrity culture, time zones. Last week got me thinking about manners movies, and I’m fascinated right now by the ways etiquette can create this sort of (non)doubling: how two people can perform identical social behaviors for radically different purposes, and how two separate observers, encountering those identical performances, might come to two completely different interpretations, neither of which are correct.

Etiquette can play this magic trick because it defines action, not sentiment; in other words, it serves to sublimate a person's actual thoughts into an orderly mode of behavior1. Once you know the proper etiquette for a given situation, you don’t have to worry about your feelings upsetting the apple cart. Two people, both seething with rage, can hash out a conversation over a polite meal without ever discussing what they’re enraged about. You can call this oppressive and dishonest, but anyone who’s seen a Maggie Smith movie knows that manners can be a method for pouring all your hatred into an unobjectionable flurry of pleasantries. As our greatest living American philosopher Judith Martin puts it, “etiquette [is] magnificently capable of being used to make others feel uncomfortable.”2 You just have to know how to do it.

Rungano Nyoni's second film, On Becoming a Guinea Fowl, is in many ways a film about manners: in this case, those that define Zambian funerals. A young woman, Shula (Susan Chardy) finds her Uncle Fred dead in the road; instead of crying, we see something close to an eye roll as she realizes that she's going to have to go through the extended motions of grieving for a man she doesn't care about. Most of the film centers on Shula and her cousins struggling to properly engage in the mourning process, which in Zambia includes lots of crawling around on your hands and knees, moaning. Shula’s lack of engagement invites significant disdain from the older generation, who know how to make a spectacular show of sorrow whether they’re feeling it or not.

This is fascinating to watch from a culture where mourning means awkwardly saying some version of "my condolences" and maybe sending a card. If only I had a prescribed way to behave when something as incomprehensible as death rears its head - maybe I’d do something with my feelings other than write movie reviews about them.3 Shula doesn't seem to agree. At first, we might assume her opposition stems from being young and educated, uninterested in perpetuating the repressive expectations of traditional Zambian women. But as the film progresses, we learn more about what’s going on within her family; without spoiling anything, it’s a whole lot more than we initially expect.

Shula’s scowl, held in a constant state of rigid disgust, defines the film until a scene, about two-thirds through, when Nyoni pulls off a remarkable shift. It's the moment when the identical objects of etiquette are split open, when we suddenly realize that the intent inside the mourning rituals has been, for lack of a less Catholic word, transubstantiated into something else. Nothing is made explicit, but everything is revealed, and along with it comes a pathway into propriety. It's a moment of shattering empathy, completely veiled in manners, moving and unsettling and ironic all at once. Is it a release valve, or a cover-up, or an invitation into a world where every polite action is a code for screaming? All three people I saw this with experienced it differently, and, as much as I hate to agree to disagree, I think impenetrability is probably the point.

I don't want to write more about this movie until more people have gotten an opportunity to see it. It’s probably a masterpiece. Susan Chardy and Elizabeth Chisela are incredible. DP David Gallego (who also shot Nyoni’s first film, the similarly excellent I Am Not a Witch) continues to pull off cinematic magic tricks, including out-of-focus backgrounds that linger after the foreground drops out and unbalanced long shots that allow inessential obstacles to block off most of the action. I realize these are not flattering descriptions, but I swear, it’s really cool. There's a scene of a pool party rave in a public library. The Youtube trailer still features a woman dressed as Missy Elliot with a man covered in sanitary pads standing over her shoulder. Go in without knowing any more than that. You'll laugh, you'll cry, you'll think about the relationship between manners and sacramental theology - what more could you want?

A New Yorker writer describes three scenes in movies that she believes are perfect examples of the recent epidemic of "literalism." A New York Crimes reporter begins her piece with a list of anecdotes of people laughing during movies that she doesn't think are funny. A Vulture critic identifies three films that have one actor playing two roles to demonstrate a disturbing uptick in iterative character design.

I made up the last one because I needed three examples to make it seem like there is an annoying trend in film criticism that I can frame as an apocalyptic event.4 But really all I want to do is complain about two recent articles that deploy similar rhetorical tricks to make stupid arguments about the current state of cinema.

The first is Namwali Serpell's article for the New Yorker about the crisis5 of literalism. Literalism seems to be an indefinite characteristic of any film that Serpell doesn't like, which in 2024 is everything other than Conclave. "When I say literalism, I don’t mean realistic or plainly literal," she writes. "I mean literalist, as when we say something is on the nose or heavy-handed, that it hammers away at us or beats a dead horse."

For starters, I am confused why "literalist" is the term Serpell lands on for "on the nose," because what she seems to dislike are ham-fisted metaphors, which are definitionally not literal. But this is shooting misused literary devices in an Alanis Morissette barrel. Serpell is concerned that contemporary film has a distrust for its audience and that it spoon-feeds us glaringly obvious signposts to make sure we're watching things right. She structures her article by moving down the line of the ten films nominated for Best Picture this year and demonstrating why they're unfit for human consumption. I don't entirely disagree with her. The Substance and The Brutalist are deeply obvious movies - though again, they're guilty of clumsy metaphor, not literalism. Emilia Pèrez is maybe the case where Serpell is spot on, but Emilia Pèrez is a unique marvel that cannot be compared to anything else in the known universe. Calling Nickel Boys "sentimental" is about as forced as you can get, and when you have to toss in the line in Anora when someone says "Cinderella!" and go after I'm Still Here for including Super-8 footage, you should know that your argument is dead.

Serpell's overall point is that many new movies are dumb and that this reflects various elements of our culture that are bad. Which I obviously agree with - we live in a dumb and bad culture full of garbage movies. But getting into the "movies used to be good" head-space is crazy when you look at the history of movies. Starting with movies that won Oscars. Was Life is Beautiful subtle? Is Braveheart a masterpiece of ambiguity? There are movies for smart people and there are movies for stupid people, and all of those people are actually the same; they just decide which version of themselves they want to have stimulated when they sit down to watch a movie.

How then will this smart/dumb audience respond when they go to the movie theater? According to the New York Crimes, they’re laughing too much at things that aren’t supposed to be funny. Crimes staffer Marie Solis seems to think, contra Serpell, that movies are too ambiguous these days - at least for stupid baby audiences who laugh every time they see something uncomfortable or unrealistic on screen.

I can imagine that, in certain spaces frequented by New York critics, audiences tend to laugh more at complicated movies than they would at the local AMC. I've only observed abundant audience laughter in re-screenings of acclaimed art movies in movie nerd theaters: the crowd at the Trylon in Minneapolis was laughing at Eyes Wide Shut earlier this year like it was a Happy Madison joint. When you've seen or read about a movie a few times you tend to be less caught up in the moment and more amused by the craft of the film. There's surely an uptick in people who think they know a lot about movies, especially at independent New York theaters - and I'm sure this come out in their audience behavior. But also, all of the movies that Marie Solis focuses on are funny: Nosferatu is camp, Babydoll is silly, and Anora self-identifies as screwball. Maybe people are laughing at these scenes because they're funny.

The only real cinematic trends, as far as I can see, are the proliferation of slopcore and people staying at home watching whatever bullshit is available on streaming instead of going to the theater. Both of these things have been written about to death, and both of them are sort of the same thing. Why do we need to pretend that there's anything else insidious happening in the world of cinema? The majority of inappropriate laughter is coming from people who are at home right now enjoying The Electric State. Movies are no more literal now than they were in 1925 or 1996 or 2022. And people are as confused now about whether something is funny or not as they were watching Buster Keaton movies. It's weird to sit in the dark with a bunch of strangers and watch something made by someone none of you know. There will always be bad movies and there will always be dumb audiences. And there will always be apocalyptic culture articles. I think we’re all going to be okay.

Thanks for reading this week’s installment of life is disappointing. If you found this review slightly less disappointing than the rest of your life, consider liking, commenting, I guess pledging me money, or (probably most usefully to everyone involved) subscribing. Subscribing will get you exactly what you get here but sent to your email inbox. You can even send it to your spam. I’ll be back next week with a review of something - maybe Eephus? Or the Steve Coogan penguin movie? Probably not Working Man. We’ll see.

This is why etiquette serves as such an effective co-conspirator with cinematic spycraft (i.e., Black Bag): etiquette masks intent with behavior, and in doing so serves as a perfect cover for deceit. You don’t know who’s scamming who when everyone is behaving within the laws of politeness. This is part of the reason why the UK produces great spy fiction and the US does not.

Miss Manners’ Guide to Excruciatingly Correct Behavior, p. 7.

Is The Last Psychiatrist cancelled? I assume he’s probably a fascist now or something. But this post is seared into my head whenever I think about funerals and probably deserves a citation.

But there really are a lot of movies right now where one actor plays two characters. I looked up the Wikipedia list and this certainly isn’t a recent development, but three in one month seems like a historic high. But maybe doubles are just the CGI monkey of 2025.

In an earlier version of this piece I implied Serpell used the term

”crisis.” That’s unfair - her essay just calls it a “plague.”