we dont need another hero

is the future of cinema cheap movies, and is that OK? // boys got to jupiter shows the way forward // 20 fall films I'm not that hyped about (and 5 that I am)

My goal with this newsletter is to write about new films as they reach general release and to feature seasonally appropriate commentary on other cinematic events and interests. This week we’ve got wonderings about the future of movies: the speculative future, kicked off by writing from Fran Hoepfner and a film from Julian Glander, and the immediate one, kicked off by Venice, TIFF, and Telluride. This newsletter comes out every Friday, which this week means Friday.

I enjoyed my fellow class-of-2013-moved-to-New-York-to-become-a-writer-got-a-job-in-food-service-instead Substacker Fran Hoepfner's post about not making money last week. Fran’s main point is that writing for money is not a good plan, but I found her endnote about the future of cinema to be the most interesting part of her piece:

When I am asked about the future of “the industry” — which industry? most of them, I guess — I think of small money as the driving force. Cheap zines, small presses, novellas, independent sites, microbudget cinema, etc. I do not think about AI, which is ugly, but $10,000 films with 58 minute runtimes, which are ugly in a different way that is actually so beautiful and yay. Most everyone I know who is working in this space is happy, albeit stressed and broke, which is kind of the best you can hope for — at least for now.

This is the sort of optimistic take you don’t get enough of these days. The critical world - myself included - spends so much time worrying about box-office numbers and media corporation mergers, and it’s worth it to ask why. Why should I care about the financial success of movies? The economic realist argument goes that movies can only exist with studios, and the only result of plunging box offices will be the eventual replacement of cinema by either AI slop or nothing.

To which I call bullshit. It has never been easier to make a movie, and there have never been more people who want to do it. For starters, pretty much everyone has a sophisticated digital camera on their person at all times - cameras that have made a Sean Baker film, a Steven Soderbergh film, and a Danny Boyle film. It’s not hard to get your hands on a slightly more sophisticated handheld, and - more importantly - it’s possible to download free editing software, chop up your footage, and slap together something beautiful. The same goes for sophisticated graphics editors, sound recording, and publishing platforms. Obviously the cost of studio films has ballooned, but that’s because of the massive expanse of industry staffing and the outrageous price of big-ticket names. Unions are good and I believe in people getting paid - and it’s possible now to make a movie with your friends that would have been pioneeringly glossy in 1975 for about half the cost of a 1975 indie.

Take two examples from 2024. The Brutalist is, imo, one of the worst films of that year - and, it’s a three-hour VistaVision epic that looks and sounds like $200 million bucks, made for about $10 million. This is incredible and would have been impossible prior to modern editing and recording technology. It netted $40 million, which it couldn’t have done without the major studio distribution it picked up after Venice, but still - it’s a low-budget, independent success made at a scale and a quality previously limited to major-studio releases.

The other is Flow, a film made entirely on free digital software for a handful of millions that far outstripped the beauty and pathos of any of its major-studio contemporaries (Inside Out 2 cost $200 million; The Wild Robot cost $78 million). Flow isn’t exactly the result of a guy sitting on his laptop doinking around with free software: it took five years to make and was funded by a boatload of European government agencies and art associations (the production title-card sequence is insane). But once again, it’s an independent labor of love created on a fraction of a Disney-Pixar budget that contributes vastly more to the art of digital animation than anything that studio has put out in years.

Two movies aren’t a trend, and the overall current of present production is stupid, expensive bloat. But I don’t think it’s crazy to compare this moment in cinema to the end of the 1950s. The 1950s produced tons of overdone genre epics - a handful of them are immortal classics, but for the most part the studios pumped out expensive crap that means nothing 75 years later. The 1960s brought handheld cameras, slapdash editing techniques, and other art film innovations from outside Hollywood, made by people who were previously unable to make films - and changed the way we see the world, in my opinion for the better.

I’m not arguing that we’re in a New New Wave of cinema, but I do think we could be capable of it if we wanted to be. The relevant technology isn’t AI (boring) but democratized access to digital and mental processing power. We have a million people who can and want to make movies, either on their computers or on interesting analog artifacts that they can access at relatively low expense. Studios continue to dominate what we see, so it’s difficult to say how much is happening outside that system. But if that system were to collapse - say, by going through a series of mergers that ultimately result in a bloated monopoly that can’t produce anything but slop supported through artificial market manipulation - we’d still have the technology, the knowledge, and the desire to make and watch movies.

I don’t think the independent spirit can render the studio system irrelevant - at least immediately - but I do think the studio system could render itself irrelevant if it keeps putting crass capitalism over art.1 Would this be so bad? Films would become smaller, messier, probably less pure-pleasure enjoyable. Distribution would tank. There would be no more movie stars.

And - people would keep making movies, because movies are really fun to make, and people really enjoy watching them. Losers would continue to write about them. Films and film criticism would continue to have political, artistic, and moral value. Art survives the collapse of economic systems. I don’t think that’s a hopeful, romantic statement, it’s just literally true. People still paint murals and put on plays and perform classical music and participate in various forms of dance I don’t understand. They even write novels. None of these art forms are massive industries, but you’d have to be a loser to say that any of them are dead, and you’d have to be an asshole to say they’re experiencing a nadir. We are programed to uniquely associate movies with industry. That doesn’t have to be the case.

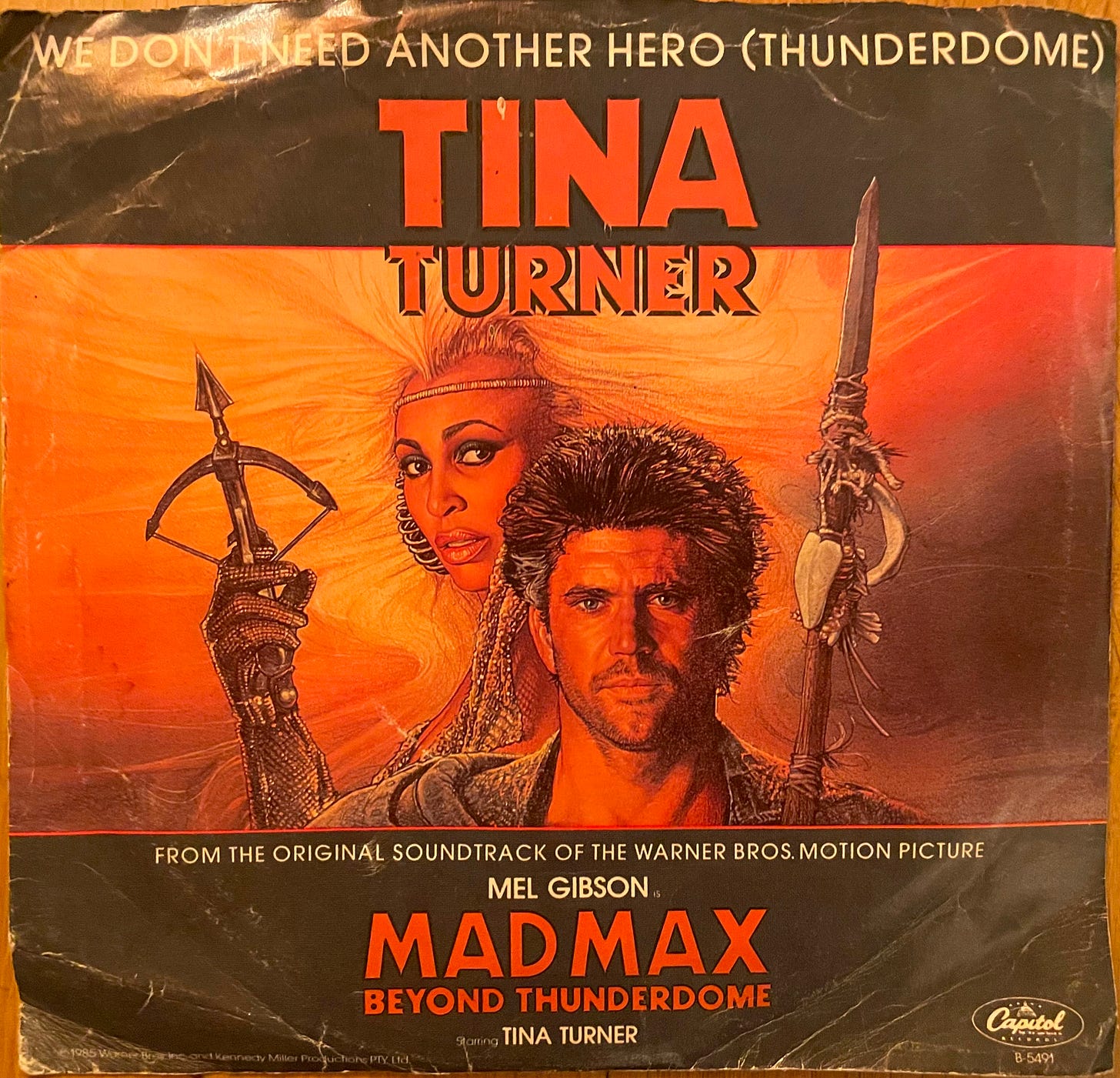

If contemplating the loss of big, beautiful blockbusters depresses you, don’t fear: we have a lot of them already, and you can still watch them, and you’ve only seen a fraction of them. Even if all the servers are wiped clean by some interesting tech disaster, there will still be the libraries of all those freaks who buy Blu-rays, and all those even freakier freaks who preserve film prints. If I live in a future where I have to pay some nut across town $5 every time I want to watch a Wong-Kar Wai movie, fine. And if I make it to one where the Grandview only screens $10,000 films made for the Twin Cities market by the next generation’s equivalent of the Coen Brothers, and I have to travel to Chicago to watch a scratched-up print of Beyond Thunderdome that only gets screened every ten years - you know what, I’m ready for it and I embrace it.

What could this cheap, low-distribution future of cinema look like? We have a prime example in somewhere between 5 and 20 theaters right now in Julian Glander’s Boys Go To Jupiter. Glander describes his film on Letterboxd as:

“Life hack: u can make a movie with ur friends on ur laptop and that movie can go on to screen at 30+ festivals and open in 40+ theaters across the US starting August 8th. Try it some time!”

Heck ya. Glander’s friends are a whole lot more connected than mine2, but I don’t think he’s overselling the unprofessional quality of this production. Boys Go To Jupiter looks like it was animated on elementary digital software, sounds like it was recorded on TikTok microphones, and soundtracked by someone who spent about two hours in the bathroom thinking up pop songs. Luckily everyone involved has off-the-wall creativity, God-given talent, and an innate feel for the zeitgeist - and the result is one of the most enjoyable films of the year.

At it's heart, Boys Go to Jupiter is a classic disaffected-youth movie: four kids in Florida, three of them content beatboxing at the beach; one of them, Billy 5000, infected with the grindset mindset and preoccupied with making $5,000 from food-app deliveries. His life changes forever when he delivers to beautiful? (everyone looks like Playmobil, so it’s hard to tell) orange-juice heiress Rozebud Dolphin. She introduces him to economic concepts that make him question his gig-economy preconceptions - and also to a sentient blob that may or may not be an angel.

Boys Go to Jupiter is not a major achievement in animation or storytelling. It's a surrealist coming-of-age story in the visual style of Adventure Time and Tim & Eric, set to the key of Orange County and Dazed & Confused. But its songs are beautiful, its sentiments are real, and its humor is charming and occasionally incisive. The visuals pingpong between disorienting absurdity and quiet beauty. People are flattened into talking car windows, food in consumption is rendered as unsettling bubbling around the mouth. The landscape is a collage of vaguely geometric tubes in oranges, purples, and greens. And every once in awhile Glander hits on an image of soaring bliss that rises above the sardonic setting, or stumbles into musical moments of Psychocandy-esque genius: “Tastes like heaven / tastes like honey / tastes like piles and piles and piles of money.” Stuff like this makes whatever youth is left in my soul swoon.

I’m curious how this film will play with kids, who I suspect might be sick of watching themselves get killed in dystopian sporting events. I wish more of them could see this. Or scratch that, I don't care - a few kids will see it, be inspired by it, talk about it too much, show it to their handful of friends who care, and remember it forever. And maybe someday they’ll make something inspired by it, get it into ten or fifteen theaters, and be happy.

As hopeful as I am for the long-term future of cinema, I’m slightly less inspired by the immediate one. We're coming up on Oscar-bait season, and though the hype is strong, I’m not excited about the slate. Park Chan-Wook, James Cameron, Kathryn Bigelow, Noah Baumbach, both Safdie brothers, Brady Corbet, Paul Thomas Anderson - all important filmmakers. I’m just not particularly interested in what they have to say or what they’ve contributed to the craft of filmmaking. Which I guess is a diplomatic way of saying that I hate a lot of what they’ve done and find their contributions to the discourse to be stupid/objectionable.

But directors contain multitudes, and you’ve got to get excited about something. So here we have it: in reverse order, my fall hype rankings from “I am politically opposed to the existence of this movie” to “might be a masterpiece.”

WILL NOT WATCH

Jon Chu, Wicked: For Good (21 November). Do not care.

James Cameron, Avatar: Fire and Ash (19 December). Do not care.

Scott Cooper, Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere (24 October). This makes me want to break my copy of Nebraska in half.

Kathryn Bigelow, A House of Dynamite (10 October). I don’t like Bigelow, I don’t like movies that sell themselves on their supposed military accuracy, I really don’t like panic attacks released straight to Netflix.

Guillermo Del Toro, Frankenstein (17 October). I don’t like prestige monster movies released straight to Netflix either.

I GUESS IF I HAVE TO

Bradley Cooper, Is This Thing On? (19 December). I have no conception of how this film could possibly be good.

James Vanderbilt, Nuremberg (7 November). I struggle to imagine that the guy who wrote The Amazing Spider-Man 2 is going to give this subject unique or thoughtful treatment.

Richard Linkletter, Nouvelle Vague (31 October). Thinking about this movie makes me want to rewatch Breathless. Everyone should rewatch Breathless.

Luca Guadagnino, After the Hunt (10 October). This didn’t get much love at Venice and seems like a bad version of TÅR, but Luca is a good enough time and Julia Roberts is a big enough get that I’m interested in what happens.

Benny Safdie, The Smashing Machine (3 October). Do we need this? I guess The Rock says we need this.

NO FAITH BUT LET’S GO

Derek Cienfrance, Roofman (October 10). This seems dumb, but I’m curious why Cienfrance is making it and I'm a big believer in Kristen Dunst.

Noah Baumbach, Jay Kelly (14 November). I find Baumbach to be one of our most tiresome beloved writer/directors. His fans are down on Jay Kelly as a sentimental departure, which makes me wonder if this will be the one that finally does it for me.

Lynne Ramsay, Die, My Love (7 November). Only the fall’s third most punishing film about parenthood.

Mary Bronstein, If I Had Legs I’d Kick You (10 October). Only the fall’s second most punishing film about parenthood.

Ronan Day-Lewis, Anemone (3 October). I suppose I too eagerly await the return of Daniel Day-Lewis.

CAUTIOUS BUT CURIOUS

Claire Denis, The Fence (no set release date). Honestly, this looks boring, but I’m ranking it high out of loyalty. Late Denis is not my favorite Denis, and I wonder sometimes if what I actually love is her collaboration with Agnès Godard, who she hasn’t worked with since 2017. We’ll see if this even gets U.S. distribution. I don’t see droves of Americans running to it.

Park Chan-wook, No Other Choice (no set release date). The plot seems trite and unnecessarily nasty, but I usually feel that way about Park Chan-wook movies. Ranking this high on accolades alone.

Yorgos Lanthamos, Bugonia. I’m worried that I’m sick of these guys’ shit.

Josh Safdie, Marty Supreme (25 December). Nothing about this film excites me, but I am as susceptible to hype as anyone.

Mona Fastvold, The Testament of Ann Lee (no set release date). This is Fastvold and Corbet’s follow-up to The Brutalist, in my opinion one of the worst pieces of screenwriting of the 21st century. But it’s scored by Daniel Blumberg, the guy who scored The Brutalist, in my opinion one of the best scores of the 21st century. He describes it as the “most extreme” project he’s ever done. Also, it’s a musical. It supposedly features multiple prothestic vaginas and is committed to portraying birth as “real and direct and graphic and unapologetic as possible.” I’m ready for this to be insufferable but also I think this is sort of why movies are made.

READY TO GO

Chloé Zhao, Hamnet (27 November). Sure seems like a bad time! Thankfully my favorite thing in all literature is the Hamlet/Hamnet chapter in Ulysses, so I can academically insulate myself from the emotional devastation this film is supposed to wreak and spend my time thinking about Zhao’s contributions to the Joycean conversation about artistic transubstantiation.

Kleber Mendonça Filho, The Secret Agent (26 November). This sounded boring until I found out it takes place during carnival. I think I’ve been unfairly conflating it with last year’s I’m Still Here, but it seems like a much more exciting way to deal with the same real shit.

Jafar Panahi, It Was Just An Accident (15 October). The season’s other foreign political thriller, and it seems like it’s got it all. Excited to dig into Panahi’s filmography, excited to talk about the politics and the artistry of Iranian cinema, excited that this is Serious Cinema with a 105-minute runtime.

Joachim Trier, Sentimental Value (7 November). I think this might be my autumn of Trier, I guy who is speaking to my soul in a way that no one else is hitting in 2025. I’m trying not to convince myself that this will be a masterpiece before I actually see it, but it sure does look like a masterpiece.

Paul Thomas Anderson, One Battle After Another (26 September). I can’t help it, I’m excited. I believe in Leo. I believe in Benicio. I even believe in Sean Penn. I want to hate them all, but dammit, they’ve all got It, and I’m ready for this to be The One.

Lots to be said in the coming weeks. This is the time of year that it feels worth it to have devoted far too much of my time and energy to watching and writing about movies. The onslaught starts next weekend. Buckle up.

Thanks for reading *life is disappointing.* If you found this newsletter slightly less disappointing than the rest of your life, consider liking, commenting, sending me money (thanks!) or subscribing. Subscribing will get you exactly what you get here but sent to your email inbox. Come back next week for a very special episode about MEGADOC! and a one-year retrospective on the most important cinematic event of 2024.

If I were a radical theorist I would create a graphic that charts the balance between capital and artistic relevance, but the gist would be that, though a publisher is primarily driven by profit margins, an art-product can only be successful if the art is at least a little bit good. AI art is profitable, but it is - and I truly think it always will be - *bad*. Over-investment in slop will kill an industry that depends on human consumption, unless humans are truly reduced to robot slop pigs - which they won’t be, b/c The Matrix is a silly movie, not political philosophy.

Boys Go to Jupiter’s insane cast list is a who’s-who of the past 20 years of a certain type of internet fame: Jack Corbett and Janeane Garafalo from NPR, Tavi Gevinson from Style Rookie; king of Letterboxd Demi Adejuyigbe; filmmakers Julio Torres and Eva Victor; alt comics Sarah Sherman, Elsie Fisher, Grace Kuhlenschmidt, Joe Pera, Cole Escala, Chris Fleming . . . if you haven’t contemplated a para-social relationship with someone in this cast, you probably didn’t go to liberal arts school betwen 2005 and 2020.